Roger Cauvin provides a briefing how to develop, communicate, and get agreement on product strategy so that the product team is empowered.

Roger Cauvin: Unlocking the Power of Product Strategy

In this session, Roger Cauvin gives a briefing on developing and refining product strategy. Roger explains the importance of having a product strategy and how it can guide decision-making within a company. He discusses various tools and artifacts that can be used to develop and communicate product strategy, including:

- Lean Canvas

- Competitive Mindshare Map

- Persona

- Product Roadmap

Roger emphasizes the need for experimentation and customer feedback to validate and refine the strategy. He also addresses questions and concerns from the audience about communicating strategy and gathering feedback. Overall, the transcript provides insights into the process of developing and implementing a product strategy.

Slides: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1nlbvclIQvz_rszt_o0NesBMjf26Gy0jcTWv1UwIX_So/export/pdf

Edited transcript

Sean Murphy: Hi, this is Sean Murphy of SKMurphy. I’ll be the emcee for today’s briefing on developing and refining product strategy. We’re fortunate today to have Roger Cauvin giving the briefing. Roger has 35 years of experience in technology. He has worked as a software engineer, a product manager, and a data scientist. He leverages his accumulated wisdom as a consumer scientist at Viewport. Viewport envisions a connected compassionate world where consumers and advertisers both benefit from online experiences.

Roger Cauvin: Thank you, Sean. I am here to share my thoughts about product strategy: the why, the what, the who, and the how. Let’s start with why you need a product strategy–how it will benefit your business. Some of you may have experienced the spreadsheet or the scorecard approach: your team puts together this big spreadsheet with all the different things you could work on next and scores them according to various criteria. The scores are added up–perhaps some criteria are weighted more heavily than others–to determine what features are most important to build. I’ve experienced this many times. It doesn’t work. It usually indicates your team needs a product strategy or they are ignoring a product strategy that you have.

Sometimes, organizational dysfunction causes your team to feel like they need to make everything objective using numbers. When your product strategy is clear to every team member, they understand the company’s decisions and can use them to guide priorities. That’s one critical reason that a product strategy can help your company. Two other ways it can help are by guiding how to describe the product and identifying which prospects to pursue.

What is a product strategy?

Roger Cauvin: In my view product strategy lies on a continuum. It’s a set of decisions, designed to achieve a goal, that provide a framework for making lower-level tactical decisions. One example of the key decisions I like come from Ash Maurya’s Lean Canvas:

- Who is the Customer (and Who are likely Early Adopters)?

- What is the Problem?

- What is Our Solution?

- What is Our Unique Value Proposition?

- What is our Unfair Advantage?

- What are Key Metrics we can use?

- What Channels can we use to reach our customer?

- What is our Cost Structure?

- What are our Revenue Streams?

When I came on the scene at my company, Viewport, my executive team was very strategic already, but they hadn’t written any of it down. It was all in their heads. And so I was able to facilitate several of these sessions and capture what was already in their head and get the assumptions down, get these strategic assumptions down in a lean canvas. So those are the sorts of people that you want in the balloon. You want those people who have market knowledge, who could be anybody in your company and the executive team.

Competitive Mindshare Map

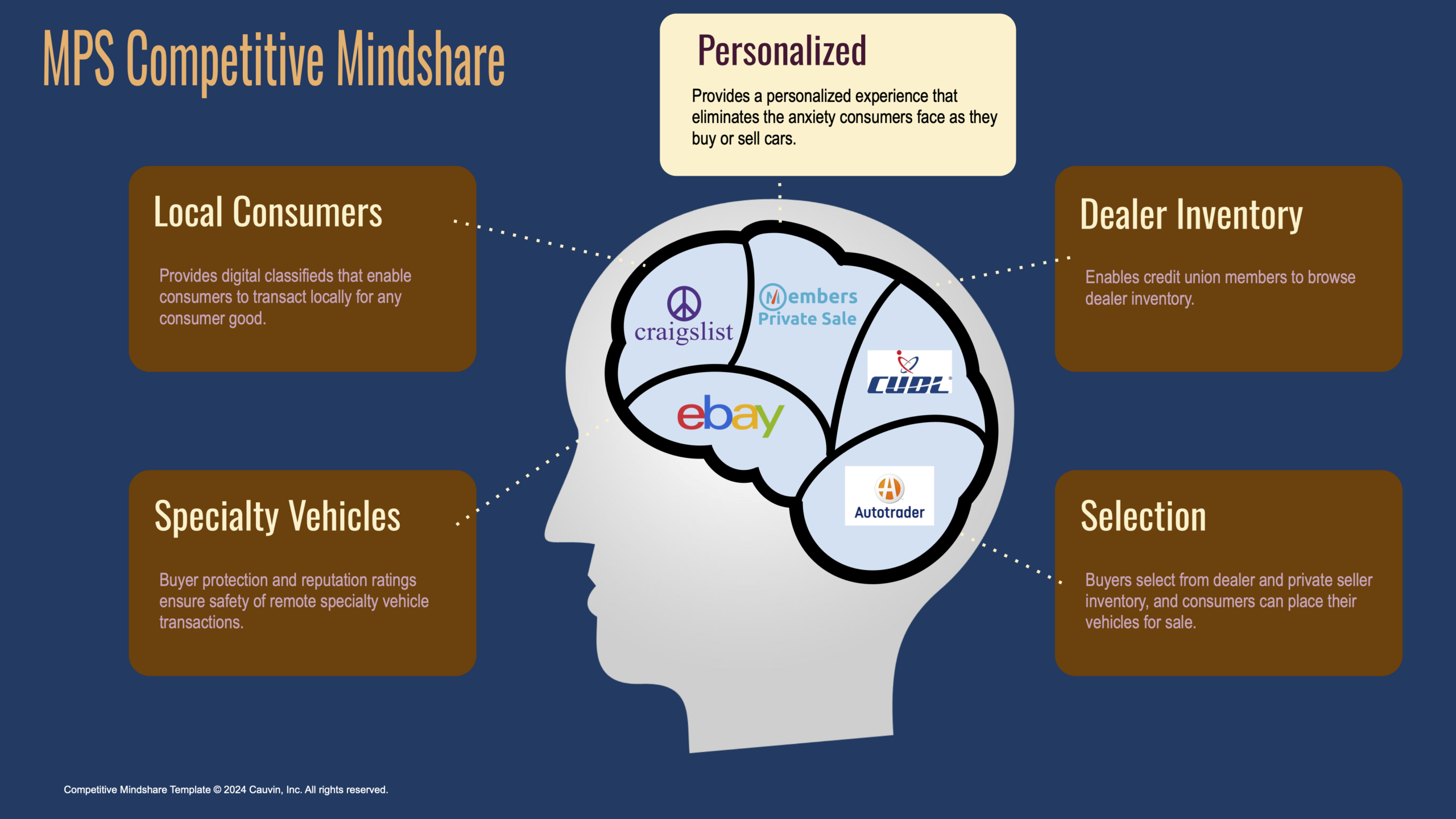

One tool you can use to create and capture your product strategy is the lean canvas. Another valuable tool is the competitive mindshare map, which helps determine your unique value proposition. This map involves taking the customer’s perspective and mapping out the territories that your competitors and you own within the mind of the customer. It draws from Al Ries and Jack Trout’s book, “Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind,” which emphasizes that the customer’s mind can only retain a limited amount of simple information.

The competitive mindshare map visualizes the different marketplaces and their perceived categories in the customer’s mind. For instance, in the context of buying and selling cars, it highlights how various marketplaces are perceived. Craigslist, for example, is primarily seen as a platform for local consumer transactions. This visualization helps businesses understand where they stand compared to their competitors and what unique space they can claim in the customer’s mind.

eBay is known for specialty vehicles, while other platforms dominate categories like dealer inventory and selection. Each company has strengths and unique value propositions that occupy specific territories in the customer’s mind. To succeed, you must acknowledge these established positions and identify open, unoccupied spaces representing your unique value. This approach helps you find and claim a distinctive position in the customer’s mind. This example is based on a company I worked for many years ago.

Persona

Another strategic tool in this process is the creation of a persona, a detailed, fictional character representing your target customer. This helps guide your team in making tactical decisions.

We identified a primary persona named Lisa. Lisa became a central figure in daily discussions and decision-making processes. Each decision and item on the roadmap was evaluated through the lens of Lisa’s needs and preferences, ensuring that strategies and actions aligned with their target customer’s expectations.

By focusing on a well-defined persona like Lisa, the company maintained a consistent, customer-focused approach. This method provided a clear strategic framework, helping the company make informed decisions that catered to their target market’s desires and helped differentiate them in the competitive landscape.

Product Roadmap

The last strategic tool I will discuss is the roadmap, which leans more towards the tactical side of the strategic-tactical spectrum. While roadmaps are widely known, the approach here borrows from Roman Pichler’s Go product roadmap template and adapts it using Jana Bastow’s now-next-later convention. This method avoids rigid timelines, offering flexibility and generality in planning.

In a collaborative setting, the roadmap’s contents should be filtered through the lens of the primary persona, Lisa, and the unique value proposition. Items included on the roadmap must directly or indirectly help realize the chosen unique value proposition. If they do not align with strategic objectives, they should be excluded. This ensures that even a tactical tool like the roadmap is guided by more strategic decisions, maintaining alignment with the overall goals and customer focus. By integrating these strategic principles into the roadmap, the team ensures that their tactical plans support and advance their broader strategic objectives.

Strategic Artifacts

In summary, we’ve covered several strategic artifacts: the lean canvas, competitive mindshare map, personas, and the product roadmap. While there are many other possible artifacts, these are among the most essential based on my experience. It’s important to remember that these tools are based on assumptions and hypotheses. The lean canvas, for instance, includes a section for key metrics, which are crucial for determining whether the business is achieving its objectives and realizing its unique value proposition.

When considering key metrics, it’s useful to design experiments to test the impact of strategic decisions on these metrics. For example, if transactions are a key metric, you might run an experiment to test this metric without fully developing the entire product. This approach allows you to validate your assumptions and make data-driven decisions.

It’s a mistake to assume that the decisions are final once these strategic documents are completed. Instead, they should be continuously tested and revisited to ensure they remain relevant and effective. This iterative approach helps refine strategies and ensures alignment with evolving business objectives and market conditions.

Q&A with Audience

Roger Cauvin: With that, I think we are open to questions. I can start by addressing Deborah’s question about communicating the strategy to the larger set of people in the company who might not have been at the stakeholders’ table, capturing the product strategy in some of these, using some of these tools. So I would be very interested in hearing Deborah’s more about Deborah’s experiences, maybe both somewhat successful observing somewhat successful efforts to communicate strategy versus maybe some of the unsuccessful attempts. I think the types of tools and documents that I presented here, like Lean Canvas and Competitive Mindshare Map, can help in a conversation about strategy. Personas can be helpful because they are designed to be a recognizable person that you could post in every office to remind people that this is the person we are targeting and are providing value for. So that’s another thing borrowing from the UX world that can help communicate at least part of the product strategy.

Sean Murphy: So Deborah, have you worked with a lean canvas or a positioning map before?

Deborah: I have not personally been in a position to be the one that structures that, but I have worked in companies that use the lean canvas as their way of thinking about the startup and getting that first thinking. I also wanted to address the question about good and bad experiences. I’ve worked in a number of different organizations of different sizes. One example that comes to mind as a good experience was a venture-backed startup with a product market fit. They were reaching scale, and I saw them clearly communicating their vision of the problem we were trying to solve. They explained the difference between the user and the buyer and how we would appeal to each, particularly how appealing to the user will create pull from the buyer.

Those conversations were fairly successful. It was a smaller organization, so they only needed to communicate through a couple of layers of employees. I’ve worked in very enterprise B2B sales-driven companies, and there, the strategy was–arguably–that we do whatever the next big customer says will get us the sale. There was a longer-term strategy, but how we operated pulled us from sales opportunity to sales opportunity. Deeper in the organization, it was harder to make decisions. My question was based on larger organizations with more layers where it seems harder to get the word out. This size makes it hard to distribute the decision-making because people don’t have the rubric to know why A is more important than B in the bigger scheme of things.

Roger Cauvin: It’s a very common problem. One thing it makes me realize about my company is that we have a culture where you always have permission to ask, “why am I doing this?” Instilling that kind of culture makes it much more likely that your strategy will be shared. If somebody at my company says, “Hey, we would really like you to do this,” I have permission to ask, “Can you give me context around that and let me know what the business purpose is behind this?”

I never get smacked down for asking that question. I ask it almost daily, and I always have permission to ask it. Asking this has led to many conversations that help align our deals with the larger strategy. You might try asking that question when the next big deal pulls up.

Deborah: I love the idea of creating a pull in the organization with that permission. I’ve definitely been in situations where it would help. For example, when we are onboarding a new product manager, engineering will warn them, “Our engineers will ask you why, so have an answer prepared for when you are challenged.” Another situation is when a revised roadmap comes out: The execution team will ask, “What problems are we solving? Who are we solving the problem for?” It was delightful to see what happens when that “Why?” culture is supported. It helps keep everyone on their toes and opens up the conversation a lot. I like that answer. Thank you.

Sean Murphy: It also helps avoid a problem where people assume they understand which problem is being solved and for whom it’s being solved. Engineering proceeds well into development, at which point somebody says, “Wait a minute, I thought we were doing X!” Then someone else says, “No, no, no, we’re doing Y.”

Roger, you make this sound very easy. Are there techniques you’ve seen that encourage this culture of why or explanation?

Roger Cauvin: Good question. Fortunately, I didn’t get resistance when I started asking why at my current company. Now, at other companies, I’ve encountered a range of responses from “Happy to explain” to “Why are you asking? This is above your pay grade: please just do what you’re told.”

What I have found works best is to be patient and persistent and to work more behind the scenes in one-on-one conversations. Being a loud voice in a large meeting is counterproductive. When company executives understand the value of an “It’s OK to ask why” culture and how much it energizes a team when they understand the strategy behind a request or a roadmap, they will embrace it.

I think Deborah hit the nail on the head. When the strategy is clear, it’s easy for everyone to make day-to-day decisions. They don’t have to ask for as much guidance–“Should I do it this way? Should I do it that way? What should I do next?” A well-understood shared purpose and shared strategy make everyone more efficient.

Sean Murphy: There’s a lot of talk these days about alignment, but strategy and the discussions that lead to a shared understanding and commitment enable effective and swift execution. Too many managers confuse strategy with command and control. But knowledge work requires enlistment, and even in the military, they brief back to ensure shared intent.

Roger, I worry you are making this seem too easy. Are there other questions for Roger about the challenges of moving from individual insights and perspectives to crafting a shared strategy that everyone understands and can execute?

Roger Cauvin: I will say that if you use the tools, then the strategy is no longer abstract and poorly understood but documented in a way that provides valuable artifacts and a basis for effective action. Once you get the strategy out of the minds of the specific people who are “in charge” and down on paper, where it can be shared, reviewed, and commented on, it’s much more likely to stick. It’s much more likely that people will appreciate the strategy and align with it.

The feature scorecard I mentioned earlier does not disappear, but it is reoriented around strategy. It’s less about the level of effort, expense, revenue, deals, and customer requests. Instead, the level of support for your unique value proposition becomes the factor with the most weight.

Audience member: I have never seen a team come to a shared understanding of a strategy template in one meeting. There might be a consensus on a rough structure, but there are often many uncertainties that need to be addressed and details that need to be worked out. I normally see this process take several meetings, with thoughtful reflection required between them.

Roger Cauvin: That’s a really good point that echoes Sean’s remark, “Boy, you make this sound so simple.” It can be hard to fill out even one box. Picking the right problem or set of problems to solve is more than one meeting. Hopefully they’re unsolved or poorly solved problems in the market so that you’re the only one who’s going to solve them well.

Audience member: It’s been said before, but everything on a canvas or template is an assumption that needs testing. You need to make sure your diagnosis of the situation is correct. You have to put something out there that people can react to. You can waste a lot of time on fancy solutions when you have not determined that you are working on a problem important enough for anyone to care enough to pay for it.

Roger Cauvin: For sure! I just realized I forgot to mention the importance of open-ended discovery sessions with prospects in the marketplace. These sessions are very different from those we discussed a moment ago, which are more closed-end surveys. The discovery sessions that I find the most valuable probe for “a day in the life” of a prospective customer or prospective user. Use open-ended questions asking for descriptions or narratives, not yes or no. Meet with people you think are possibly in your target market and walk them through their day-to-day experiences that might be relevant to the problems you plan to address. Don’t steer the conversation to particular problems you want them to volunteer.

Also, never underestimate the knowledge base of people in your company. It can take some facilitation and skill to extract that information from the minds of those who have it. I was fortunate that the executives at my current company understood the problems. They had not made them explicit so that everybody could understand them. It only took a few facilitated conversations to extract and capture their insights so that they could be widely understood.

Sean Murphy: That last point is critical and poorly appreciated by many product management gurus. Many seem allergic to tapping expertise within a firm and advise product teams to talk only to the customer directly. I think it’s essential to speak to customers. Still, in larger firms, you are well served to solicit insights from customer support, sales, applications engineers, and anyone with regular contact with prospects and customers. To your point, Roger, there is often a lot of knowledge you can tap into inside your company if you ask politely. Too many product teams have the other “startup dollhouse fantasy” where they are a startup trapped inside a larger firm.

Roger Cauvin: When you ask people with market knowledge open-ended questions, it often makes them think. Sometimes, they have a comprehensive answer to the questions you ask them about the market, but other times, you raise issues they hadn’t considered. Both are useful; the latter can encourage curiosity within the company about answering some of the questions that haven’t previously been answered.

I tend to pursue both internal and external sources of knowledge in parallel. I reach out to people within the company who may possess relevant knowledge, but I also start to get out of the office and do interviews and ethnographic studies. It can be a little bit delicate when you have a sales team with big quotas; they can be a little sensitive to the idea of you accidentally discouraging a purchase they have forecast. So you have to be careful about that. But it’s good to start laying the groundwork for early conversations with prospects and customers.

Sean Murphy: Roger, did you have any final or closing remarks?

Roger Cauvin: Thanks for having me. And thanks to all who showed up. I would invite people to connect with me on the socials and feel free to ask any follow up questions via either the socials or my email address or maybe via the meetup group.

Related Blog Posts

- Frank Tisellano: “Business First” Product Management

- Mary Sorber: Raw Pasta is Not Enough

- Accidental Learnings from a Journeyman PM by Bill Seitz

- Without A Revenue Hypothesis Your Business Model Is a List of User Activities

- Feeling Lucky Is Not a Strategy

- John Nash on “Make Something that People Want”

- Strategy is a Hypothesis

- Product-Market Fit is a Fraction Not a Bit