It’s been 17 years since the Sep-11-2001 attack and almost 77 years since the Dec-7-1941 Pearl Harbor attack that started World War 2. Both attacks achieved strategic surprise and had substantial long-term effects. What follows are some excerpts from the forward by Thomas Schelling Roberta Wohlstetter’s book “Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision.”

Thomas Schelling on Strategic Surprise

“It would be reassuring to believe that Pearl Harbor was just a colossal and extraordinary blunder. What is disquieting is that it was a supremely ordinary blunder. In fact, “blunder” is too specific; our stupendous unreadiness at Pearl Harbor was neither a Sunday-morning, nor a Hawaiian, phenomenon. It was just a dramatic failure of a remarkably well-informed government to call the next enemy move in a cold-war crisis.

If we think of the entire U.S. government and its far-flung military and diplomatic establishment, it is not true that we were caught napping at the time of Pearl Harbor. Rarely has a government been more expectant. We just expected wrong. And it was not our warning that was most at fault, but our strategic analysis. We were so busy thinking through some “obvious” Japanese moves that we neglected to hedge against the choice they actually made.”

Thomas Schelling in his forward to “Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision” by Roberta Wohlstetter

The same could be set of 9-11’s foreshadowing in the earlier 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center. Tom Clancy’s 1994 novel “Debt of Honor” ends with a 747 crashing into the Capitol Building during a special joint session of Congress, killing most of the senior members of the US government including the cabinet, the Senate, the House of Representatives, and the Supreme Court. I can remember the afternoon of 9-11 thinking about the strange synchronicity between Clancy’s fictional scenario and the likely target of United Flight 93.

A Fine Deterrent Can Make a Superb Target

And it was an “improbable” choice; had we escaped surprise, we might still have been mildly astonished. (Had we not provided the target, though, the attack would have been called off.) But it was not all that improbable. If Pearl Harbor was a long shot for the Japanese, so was war with the United States; assuming the decision on war, the attack hardly appears reckless. There is a tendency in our planning to confuse the unfamiliar with the improbable. The contingency we have not considered seriously looks strange; what looks strange is thought improbable; what is improbable need not be considered seriously.

Furthermore, we made a terrible mistake–one we may have come close to repeating in the 1950s–of forgetting that a fine deterrent can make a superb target.

Thomas Schelling in his forward to “Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision” by Roberta Wohlstetter

I find this to be a profound insight: “a fine deterrent can make a superb target.” This was true of several of the opening moves that Japan made in WW2: devastatingly effect attacks on Pearl Harbor, Hong Kong, Bataan, and Singapore. All of these represented strategic bases in the Pacific established to deter Japanese military action.

Surprise, when it happens to a government, is likely to be a complicated, diffuse, bureaucratic thing. It includes neglect of responsibility but also responsibility so poorly defined or so ambiguously delegated that action gets lost. It includes gaps in intelligence, but also intelligence that, like a string of pearls too precious to wear, is too sensitive to give to those who need it. It includes the alarm that fails to work, but also the alarm that has gone off so often it has been disconnected. It includes the unalert watchman, but also the one who knows he’ll be chewed out by his superior if he gets higher authority out of bed. It includes the contingencies that occur to no one, but also those that everyone assumes somebody else is taking care of. It includes straightforward procrastination, but also decisions protracted by internal disagreement. It includes, in addition, the inability of individual human beings to rise to the occasion until they are sure it is the occasion–which is usually too late. (Unlike movies, real life provides no musical background to tip us off to the climax.) Finally, as at Pearl Harbor, surprise may include some measure of genuine novelty introduced by the enemy, and possibly some sheer bad luck.

Thomas Schelling in his forward to “Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision” by Roberta Wohlstetter

In “Cuba and Pearl Harbor: Hindsight and Foresight“, Roberta Wohlstetter observes that “the problem of warning is inseparable from the problem of decision.” I think echoes this in his line “he inability of individual human beings to rise to the occasion until they are sure it is the occasion–which is usually too late.” I think this explains the actions of the crew and passengers of United Flight 93, they had three other data points from the earlier flights that crashed that this was not a hijacking but a kamikaze mission.

The Sudden Concentrated Result of a Failure to Anticipate Effectively

The results, at Pearl Harbor, were sudden, concentrated, and dramatic. The failure, however, was cumulative, widespread, and rather drearily familiar. This is why surprise, when it happens to a government, cannot be described just in terms of startled people. Whether at Pearl Harbor or at the Berlin Wall, surprise is everything involved in a government’s (or in an alliance’s) failure to anticipate effectively.

Mrs. Wohlstetter’s book is a unique physiology of a great national failure to anticipate. If she is at pains to show how easy it was to slip into a rut in which the Japanese found us, it can only remind us of how likely it is we are in the same kind of rut now. The danger is not that we shall read the signals and indicators with too little skill; the danger is in a poverty of expectations–a routine obsession with a few dangers that may be familiar rather than likely. Alliance diplomacy, inter-service bargaining, appropriations hearings, and public discussion all seem to need to focus on a few vivid and oversimplified dangers. The planner should think in subtler and more variegated terms and allow for a wide range of contingencies. But, as Mrs. Wohlstetter shows, the “planners” who count are also responsible for alliance diplomacy, inter-service bargaining, appropriations hearings, and public discussion; they are also very busy. This is the genuine dilemma of government.

Thomas Schelling in his forward to “Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision” by Roberta Wohlstetter

Schelling’s CV at the University of Maryland lists stints at

- The U. S. Bureau of the Budget, 1945-46;

- The Marshall Plan in Copenhagen and Paris, 1948 to 1950;

- The White House and Executive Office of the President, 1951-1953.

So, he had direct and personal experience with the challenges and conflicting priorities that “planners” face in running down well-worn paths, risking a stunted strategic imagination and limited foresight. But I think this is a more realistic assessment of what’s required than more recent remarks by Cynthia Storer in “Road to 9-11”

“You need subject-matter experts whose job is only to look at the information—not to collect it, not to go to meetings, not to play politics. You need the experts to give you a sound read on what’s happening that’s free of political considerations. If you don’t get that, then it’s one of the way things kind of go off the rails.”

Cynthia Storer “Road to 9-11″

The real decision-makers are not disinterested parties; they are subject to political pressures and competing priorities. The challenge is holding them accountable for wanting to know the ground truth and being willing to take effective action. Some organizations are better at avoiding the temptation to ignore bad news–or the risk of having to acknowledge current approaches are not effective–I think it has to do with a striving for excellence and having members of the organization directly in harm’s way if the current plan of action fails. General Stanley McChrystal addressed this issue in his command in Iraq by cross-embedding strong team members in support organizations and creating a daily briefing that included key members of his direct command and support organization.

Wolhstetter’s “Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision”

Two excerpts that bear on 9-11.

“The fact that intelligence predictions must be based on moves that are almost always reversible makes understandable the reluctance of the intelligence analyst to make bold assertions.”

Roberta Wohlstetter in “Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision“

Detecting weak signals is very difficult, especially against a competitor that is masking them with ambiguity, stealth, and camouflage.

“If the study of Pearl Harbor has anything to offer for the future, it is this: We have to accept the fact of uncertainty and learn to live with it. No magic, in code or otherwise, will provide certainty. Our plans must work without it.”

Roberta Wohlstetter in “Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision“

This is her conclusion to the book. She elaborates on this in a follow-on research paper ” Cuba and Pearl Harbor: Hindsight and Foresight.”

Wohlstetter’s “Cuba and Pearl Harbor: Hindsight and Foresight”

Subsequent to her “Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision“–which originally started out as a Rand paper several years before it’s publication as a mainstream book–Roberta Wohlstetter published another RAND research paper Cuba and Pearl Harbor: Hindsight and Foresight that updates her analysis of the strategic surprise achieved by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor with lesson from the Berlin Crisis and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Here are some excerpts

“The interpretation of data depends on many things, including our estimates of the adversary and of his willingness to take risks. this depends on what our opponent thinks the risks are, which in turn depends on his interpretation of us. We underestimated the risks that the Japanese were willing to take in 1941, and the risks that Khrushchev was willing to take in the summer and fall of 1962. Both the Japanese and the Russians, for their part, underestimated our willingness to respond.”

Robert Wohlstetter in Cuba and Pearl Harbor: Hindsight and Foresight

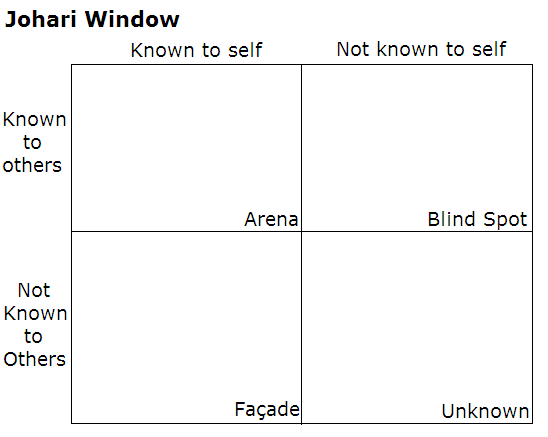

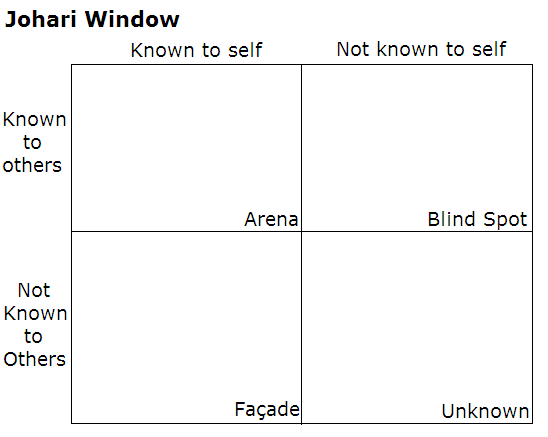

- Arena we know / they know

- risk: we think they know but they don’t

- Facade: we know / they don’t know

- true facade: we think they don’t know and they don’t

- actually a blind spot: we think they don’t know but they do

- Blind Spot: we don’t know / they know

- “fuzzy awareness” we know they know something

- Unknown: we don’t know / they don’t know – “unknown unknowns”

Lack of Planning with Fine Grained Responses Limits Flexibility and Effectiveness

“It is important to recognize that the difficulties facing intelligence collection and interpretation are intrinsic, and that the problem of warning is inseparable from the problem of decision. We cannot guarantee foresight, but we can improve the chance of acting on signals in time and in a manner calculated to moderate or avert disaster. We can do this by a more thorough and sophisticated analysis of observations, by making more explicit and flexible the framework of assumptions we must fit new observations, and by refining, and making more selective, the range of responses we prepare so that our response may fit the ambiguities of our information and minimize the risks both of error and inaction.”

Robert Wohlstetter in Cuba and Pearl Harbor: Hindsight and Foresight

In “Preventing Chaos in a Crisis,” Patrick Lagadec observes: “The past settles its accounts. …the ability to deal with the unexpected is largely dependent on the structures that have been developed before chaos arrives. The complex event can in some ways be considered as an abrupt and brutal audit: at a moment’s notice, everything that was left unprepared becomes a complex problem, and every weakness comes rushing to the forefront.” The best way to mitigate this is to do your homework in advance and work out a range of options. In 9-11 the decision to shut down the United States commercial air traffic control system was an intelligent improvisation to a threat that was real but whose magnitude was not clearly established: if there were four hijacked planes that we were aware of, could there be four more? Or ten more? The response of the surviving crew and passengers of United 93 represents a second improvised response that was the exact opposite of all of the pre-attack advice and planning for hijacked aircraft.

Signal vs. Background Noise

The “signal” of an action means a sign, a clue, a piece of evidence that points to the action or an adversary’s intention to undertake it; “noise” defines the background the background of irrelevant or inconsistent signals, signs pointing in the wrong direction, that tend always to obscure the signs pointing the right way. Pearl Harbor, looked at closely and objectively, shows how hard it is to hear signal against the prevailing noise, in particular when you are listening for the wrong signal, and even when you have a wealth of information. (Or perhaps especially then–there are clearly cases when riches can be embarrassing.)

After the event, of course, we know–like the detective story reader who turns to the last page first, we find it easy to pick out the clues. And a close look at the historiography of Pearl Harbor suggests that in most accounts, memories of the noise and background confusion have faded most quickly, leaving the actual signals of the crisis standing out in bold relief, stark and preternaturally clear.

Robert Wohlstetter in Cuba and Pearl Harbor: Hindsight and Foresight

This “hindsight bias” is the source of conspiracy theories and a fruitless search for the guilty who ignored “obvious signals.” The challenge is to remember the tremendous uncertainty and confusion in a flood of contradictory information.

SKMurphy Take

I remain profoundly affected by 9-11, this blog post was an effort to put it in an appropriate historical context of other strategic military surprises the enemies of the United States have been able to inflict. Schelling’s forward contains a number of insights that are applied not only to military conflicts but commercial competition.

Related Material

Thomas Schelling

- CV at the University of Maryland and full list of publications (PDF)

- List of Rand publications; I found his “Uninhibited Sales Pitch for Crisis Games” in “Crisis Games” offered a useful planning model for minimizing strategic surprise.

- Nobel Prize in Economics (2005) Lecture: “An Astonishing 60 Years”

- book: Strategy of Conflict (1960)

- book: Arms and Influence (1966)

- book: Micromotives and Macrobehavior (1978)

- book: Choice and Consequence (1984)

Len Deighton: Blood, Tears, and Folly: An Objective Look at World War 2 recounts the early disasters and major blunders of the Allies in WW2.

Graham Allison: Essence of Decision a detailed examination of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Albert Wohlstetter Dot Com: Roberta Wohlstetter Bibliography

More on Stanley McChrystal’s “Team of Teams” model:

- Foreign Policy: “It Takes a Network” by Stanley McChrystal

- book: Team of Teams: New Rules for Engagement in a Complex World

- book: One Mission: How Leaders Build a Team of Teams

Patrick Lagadec “Preventing Chaos in a Crisis”

Related Blog Posts

- 15 Years After 9-11, Four After Benghazi

- Pearl Harbor to 9-11 to the Panopticon

- Lee Harris’ Insights on What 9-11 Means

- Second Sight: A Meditation on Silicon Valley and 9-11

- Remembering 9-11: Our Children Will Also Live in Interesting Times

- Take a Minute To Remember 11 Years Ago

- Remembering What Happened

- Take a Minute To Remember 9 Years Ago

- Take a Minute to Recall 8 Years Ago, Part 2

- Take a Minute to Recall 8 Years Ago

- Lesser Sons of Greater Fathers

- Austin Bay has applied “the war for terms of modernity” not only to the conflict with fundamentalist Islam but also disagreements with China and Russia.