This talk is for a busy founder facing the challenges of exploring ideas and achieving product-market fit with ten to fifteen paying customers.

12 Books for the Busy Founder

Event Description 12 Books For Busy Startup Founders: spend an hour and leave with a summary of key business insights and some rules of thumb for successful innovation. You might even identify one or two books you haven’t read that will be worth your time over the summer. Sean Murphy will cover twelve books that form the basis for conventional wisdom in Silicon Valley for discontinuous or disruptive products.

About the Speaker Sean Murphy, CEO of SKMurphy, Inc. Sean Murphy has taken an entrepreneurial approach to life since he could drive. He has served as an advisor to dozens of startups, helping them explore risk-reducing business options and build a scalable, repeatable sales process. SKMurphy, Inc. focuses on early customers and early revenue for software startups, helping engineers to understand business development. Their clients have offerings in electronic design automation, artificial intelligence, web-enabled collaboration, proteomics, text analytics, legal services automation, and medical services workflow.

Edited Transcript

Hi, this is Sean Murphy of SKMurphy, Inc. I welcome you to Lean Culture. Today, I’m giving a briefing on 12 books for a busy founder.

I’d like to ask a couple of questions by show of hands or typing into the chat:

- Who’s actively pursuing a startup or in one right now?

- Who’s considering a startup or entrepreneurially curious?

- Is anybody trying to apply entrepreneurial principles in larger firms as an intrapreneur?

- Finally, any consultants?

Okay, this gives me an idea of where people are coming from.

A little about me: We started in 2003, focusing on customer development consulting and offering peer advisory groups for entrepreneurs, particularly bootstrappers. We help them find leads and close deals, aiming for early customers who become references and generate early revenue.

Here’s the bookshelf for today. I’ve found these books very helpful. They offer useful models and rules of thumb for entrepreneurs.

| Author | Book | Pub Date(s) |

|---|---|---|

| James H. Austin | Chase, Chance, and Creativity | 2003 |

| Clayton Christensen | The Innovator’s Dilemma | 1997 |

| Peter Drucker | Innovation and Entrepreneurship | 1985 |

| Rob Fitzpatrick | Mom Test | 2013 |

| Michael Gerber | The E-Myth Revisited | 1995 |

| Seth Godin | This is Strategy | 2024 |

| Doug Hall | Jumpstart Your Business Brain | 2001 |

| Ash Maurya | Running Lean | 2012, 2022 |

| Geoffrey Moore | Crossing the Chasm | 1991, 1999, 2014 |

| Sean Murphy | Working Capital: It Takes More Than Money | 2020 |

| Al Ries & Jack Trout | 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing | 1994 |

| Saras Sarasvathy | Effectual Entrepreneurship | 2011, 2016, 2025 |

This talk focuses on challenges from getting started, exploring ideas, to achieving product-market fit with 10 to 15 paying customers, before scaling. There are other books that cover scaling and the early sales processes, but those are for a different talk. The foundational books are

- Running Lean by Ash Maurya, provides the best overview of Customer Development and Lean Startup methods.

- Effectual Entrepreneurship by Saras Sarasvathy, offers the best end-to-end view of starting and growing a venture.

Other books fill in gaps. The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton Christensen, written for large companies, helps startups see the market from the incumbent’s perspective.

Discontinuous Innovation

We’ll focus on discontinuous innovation, which “breaks the mold” or requires significant changes in practice.This is where startups often need to hunt for opportunities. Established firms excel at continuous innovation, which is easier for customers to adopt, but startups must play in discontinuous spaces.

| Evolution | Revolution |

|---|---|

|

|

There are two types of change: evolution (continuous, incremental, better-faster-cheaper innovations) and revolution (discontinuous, disruptive innovations). Most successful innovations are sustaining, offering smooth transitions. Startups, however, normally must focus on discontinuous innovation because incumbents occupy most of the squares where simple or smooth upgrades are possible.

Five key concepts thread through these books:

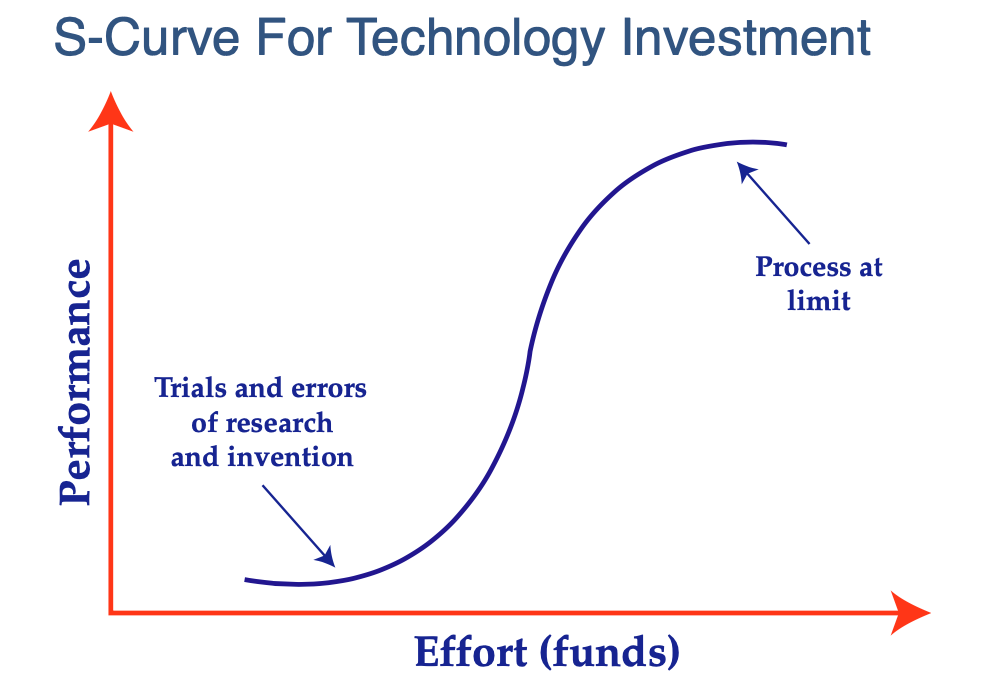

- The S-curve, showing how technology investments pay off over time.

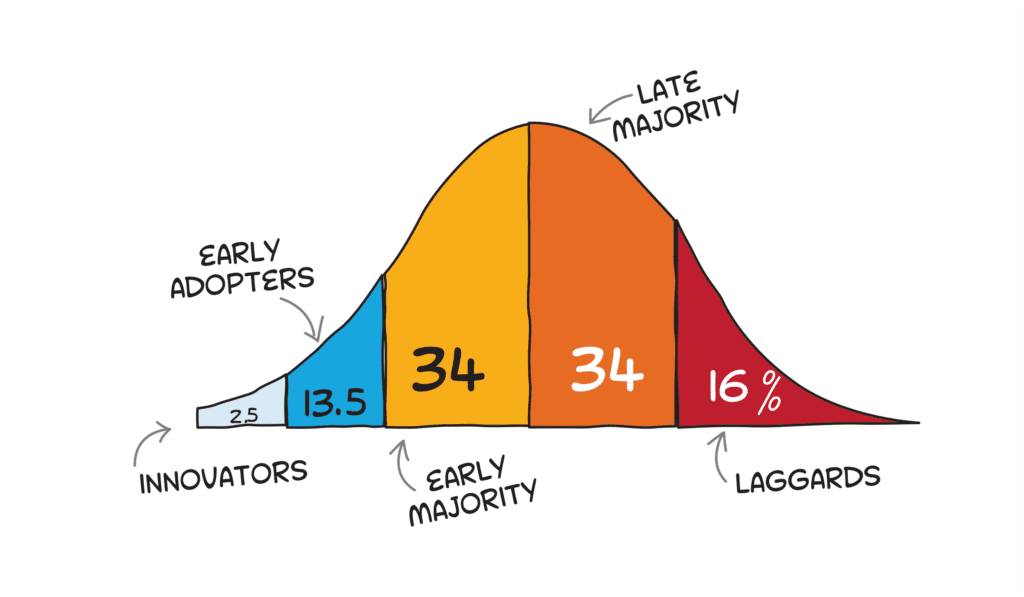

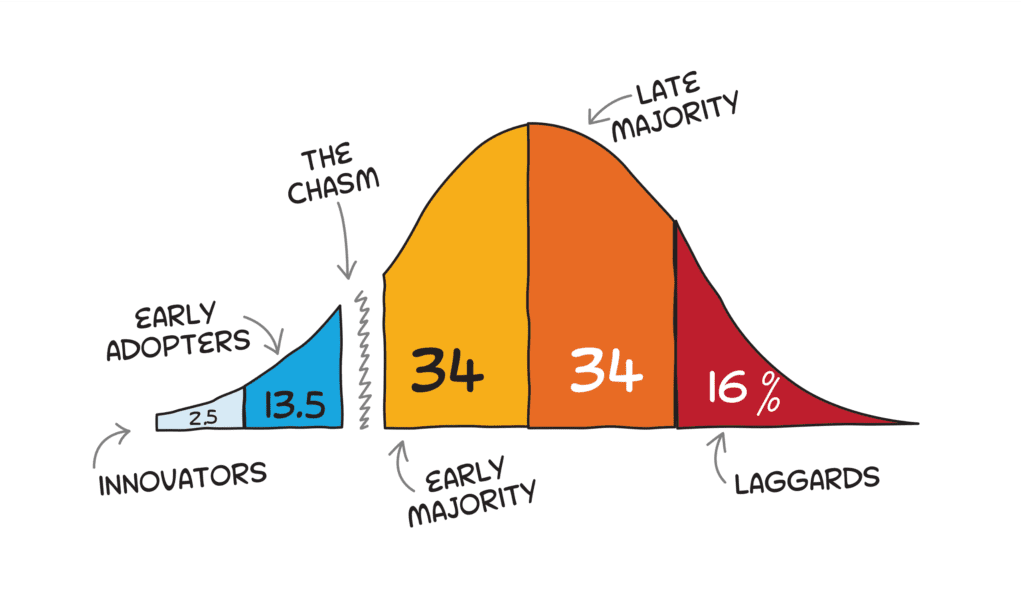

- The technology adoption life cycle, describing how technologies are adopted.

- The need for founders to focus.

- Customers want a complete or “whole” product.

- How to be systematic in identifying opportunities.

The S-Curve of Technology Development

Most technologies start with many problems that normally require trial and error to debug. They go through three phases:

- A setup cost and learning curve: most technologies don’t work very well when they first come into the world. You have to invest effort and you may discover that you have drilled a dry hole, you cannot make it work. Or you can make it work but it does not offer differentiate value because existing technologies have made more improvements than you anticipated or new alternative technologies have made more progress than you have. Ask the firms that developed bubble memory only to be obsoleted by flash technology.

- Increasing returns if the teething problems are resolved successfully. It can be challenging to predict where the inflection point lies, as success enables higher investment levels that drive further progress. It can also be challenging to detect that many of your customers are unwilling to pay for higher performance, as your most demanding customers, who are often your most profitable, continue to absorb and pay for whatever improvements you can deliver. Christensen illuminates these challenges in “The Innovator’s Dilemma.”

- A slowing rate of improvement, where increased investment yields decreasing incremental returns, and eventually leads to stagnation. Established firms tend to linger in the upper quarter of this curve to avoid the risk of switching to a new technology. Startups tend to target less desirable customers, from an incumbent’s point of view, or non-customers ignored by incumbents. A startup attacking an incumbent’s core market head-on is rarely successful. Gordon Bell refers to this as “attacking a walled city” in “High Tech Ventures,” (a great book that did not make the final cut).

Technology Adoption Life Cycle

This framework is from “Diffusion of Innovations” by Ev Rogers in 1962. Geoffrey Moore popularized it for high technology businesses in Crossing the Chasm in 1991. There are five categories: innovators go first, followed by early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. It’s a nice single parameter model for a normal distribution based on risk aversion. Moore assigned different labels to each category starting with technologists, then visionaries, pragmatists, conservatives, and skeptics. But they are the same categories.

Moore identifies a “chasm” between early adopters, who tolerate incomplete products for significant benefits, and the early majority, who demand a whole product and established market. Early adopters don’t influence the early majority, who view them as lunatic risk-takers. Early majority or pragmatic buyers want the comforts of an established market, including a complete or whole product.

I’ll just observe that Rogers disputes this even now and says that there’s real gap that Moore made this up. But I think there is good evidence for this gap when you are introducing a discontinuous innovation. It’s been my experience as well. Another difference between visionaries and pragmatics is that you don’t have to sell to visionaries, they have a transformational need in mind before you approach them.

The challenge in crossing the chasm is to find a pragmatic buyer who is in a lot of pain because they are poorly served by what’s available, and your product can help them. The trick is to offer them enough proof you can help with demonstrations, trial evaluations, case studies, and references. You can’t serve everyone initially; focus on a small, painful niche.

Drucker on Innovation

“Innovation requires us to systematically identify changes that have already occurred but whose full effects have not yet been felt, and then to look at them as opportunities. It also requires existing companies to abandon rather than defend yesterday.”

Peter Drucker in Innovation and Entrepreneurship (1985)

So, how to identify changes that have already occurred but whose full effects have not been felt? That’s a great question. Large and successful firms find it difficult to spot them, rejecting most changes that don’t support what has made them successful as outliers or random variations. Most of the time, they are right. Nothing new ever works, and most new ideas don’t pan out even after you tinker with them. But sometimes new things come into the world, and large firms find it difficult to let go of yesterday’s success and identify these harbingers.

As an aside, I was initially dubious of the LLM innovations. I had lived through the first AI winter, and the second, and I said to myself, “I’ve seen this movie and the sequel. “I don’t want to get my hopes up that third time is a charm.” But I’m becoming convinced that this time may be different. (Josh Billings offers some of the best advice on navigating the entrepreneurial landscape: “It’s not the things we don’t know that get us into trouble, it’s the things we know that aren’t so.”)

Drucker suggests that these are the most common sources of innovation:

- Unexpected developments to build on.

- Incongruities where something works in one area but could be applied elsewhere.

- Process gaps or weak links with high impact if solved.

- Changes in industry or market structure (e.g., traditional media shifting to streaming).

- Demographic shifts, predictable and impactful.

- Changes in perception or mood (e.g., sustainability trends).

- New knowledge or technology.

This is a good checklist for identifying opportunities. You should ask yourself, am I taking advantage of one or more of these in my startup. So that was a little bit about, how the world works. Let’s talk about what strategies are available to startups,

How Startups Should View the World

- Ash Maurya: Your startup begins as a set of linked hypotheses.

- Rob Fitzpatrick: How to interview customers.

- Doug Hall: How to describe your product.

- Saras Sarasvathy: Experienced entrepreneurs use five effectuation principles.

- Michael Gerber: Technology is not enough, you need reliable processes that deliver value.

- Seth Godin: Don’t run out of time or money.

Ash Maurya: Your startup begins as a set of linked hypotheses.

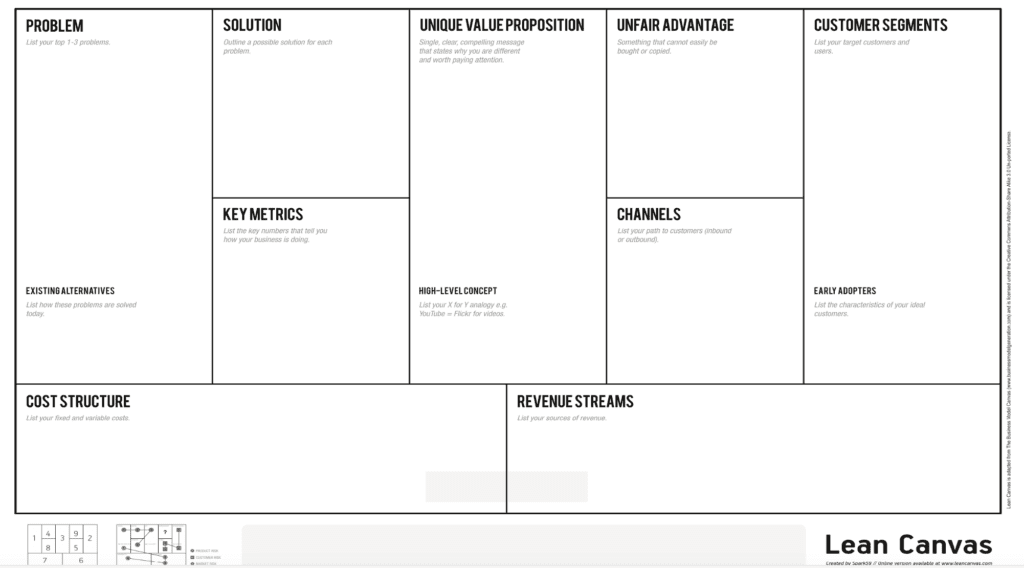

Ash Maurya’s “Lean Canvas’ improves on Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas. It offers a one-page diagram of your business model. One key point he stresses is that we are all in love with our solutions and we need to focus on the problem. We tend to focus on the better mousetrap and are surprised when the world does not beat a path to our door. We need understand who is really worried about getting rid of the mice in their house, or their warehouse, or their restaurant. Founders must understand the customer’s perspective on the problem.

The best evidence for this comes from conversations with customers, because conversations allow for surprise and the communication of nonverbal cues and emotion. This goes well beyond a survey question like “tell me on a one to five scale how important is this problem to you.”

Ash then simplified it to the “Leaner Canvas.”

| Problem List your top 1-3 problems |

Customer Segments List your target customers |

| Existing Alternatives List how these problems are solved today |

Early Adopters List the characteristics of your ideal customers |

Of all the hypotheses on the Lean Canvas, the customer hypothesis is the most important. Don’t get trapped in invention or focusing on your beta product. To figure out what people are actually willing to pay for, you have to make real offers. If you ask hypothetical questions, you get hypothetical answers, so you understand the problem, and then you have to start making real offers, offers you’re prepared to deliver on.

At Bootstrappers Breakfast®, we focus on four questions:

- What’s the problem?

- Who has it?

- What alternatives are they using?

- Who’s in the most pain and likely to move quickly?

Fast decisions are preferable to chasing big deal because they enable rapid experimentation. I have seen too many teams get “yessed to death” chasing a large deal with an enterprise. You end up with all of your eggs in one basket, unable to say no to unreasonable requests, and not developing a sense of what the range of requirements are for a given population of prospects.

How to Interview Customers

Make sure to understand the customer’s view of a problem before you talk about your solution.

- Mom Test: Don’t ask for predictions, focus on past behavior.

- How are they managing the problem now?

- How often do they experience it? What triggers it?

- What have they tried and rejected?

- Running Lean: Talk to people who recently purchased a product to solve their problem. What triggered their decision? What have they learned?

When talking to customers, avoid pitching the product first. Rob Fitzpatrick, in the “The Mom Test,” advises focusing on the problem and past behavior: how often they experience it, what triggers it, what they’ve tried and rejected, and why. Everything else being equal, the more frequently the problem is encountered, the more likely they are to be willing to pay something to address it.

Ash Maurya has a clever suggestion in “Running Lean.” Talk to people who have recently purchased an alternative solution, where recent is within the last three to six months. Ask questions to understand what triggered their decision to spend money and what they learned from using the alternative. Follow up with your own customers to ensure your product delivers.

Doug Hall on How to Describe Your Product

3 laws of market physics for products

- Demonstrable benefit

- Reason to believe

- Dramatic difference

3 laws of creativity for product team

- Explore Stimuli

- Leverage diversity

- Face fears

People consume descriptions of your product before move on to demos, evaluations, and purchase. they consume the product, agree to test the product. Make sure you can offer a clear and demonstrable benefit your target customer is likely to be interested in. Next you have to give them reasons to believe you. This can be a mix of benchmark data, testimonials, case studies, demonstrations using their data, and the opportunity for them to evaluate the product directly. And finally, as a startup, you have to be significantly better in at least one aspect of functionality or performance that they care about to get them to move forward.

A startup is also product team. I think the most important of the 3 laws for creativity is to face your fears. Solve the hardest problem first, the biggest risk to your ability to deliver results. That will tell you if you are working on the right product concept (we also address this in our 1-2-4-1 model, solve the problems most likely to sink you first). There is no advantage in doing a lot of things right but putting off the big risks.

Q: Does this mean you don’t have to build an MVP to start talking to customers? I’ve always heard it the other way.

Customers consume a description before they consume a product, and they’ll normally want a demo before they try the product. I think, at a minimum, you need a description that can be a datasheet or sketch. You don’t need a fully working product to have a valuable conversation. But you need something that you can use to illustrate the benefits that you can deliver. I think entrepreneurs have high hopes for what a demo will do. If prospects can just experience the product, they’re going to have a road-to-Damascus experience where the scales fall from their eyes and they realize they need this product immediately. But you have to make sure you understand their problem and then explain how the product can help.

Q: When you use the word demo, then that is not meant to be an MVP?

I view an MVP as a product offered for sale to solve a problem for a customer. A demo can be a piece of paper that describes the product. It can be a paper mock up that shows a key screen or a key output or report. Think about when you are getting ready to buy a car. You start by looking at descriptions, maybe a Consumer Reports buyer’s guide. You don’t start with a test drive.

Saras Sarasvathy’s Effectual Entrepreneurship Model

- Work with what you have: use current means to see what ends you can achieve. Now those ends become new means.

- Relationships are critical, and a persistent asset in assembling a “crazy quilt” for co-creation. Be helpful and as generous as you can

- Affordable loss: only bet what you can lose. Most things don’t work out, plan accordingly.

- Take advantage of surprise: make lemonade. Don’t reject the unexpected, make it an asset (perhaps in barter with others).

- Focus on what’s under your control, less on prediction. Leave early to arrive on time; have a backup plan.

Sarasvathy’s effectuation principles start with using what you have under your control to make progress. Then use those accomplishments as new means. Don’t wish for resources; work with what’s available.

The second principle points out a significant weakness of the Lean Startup mentality, which is the complete lack of attention to relationships and your reputation within a community. Relationships are critical and can become persistent assets. They allow you to build a quilt of co-conspirators that help you solve problems–as you help them solve problems–to bring a product to market. Cultivating this extended team requires you to be as helpful and as generous as you can. Most successful startups have a team, not a lone gunman, and a web of relationships that help them move forward.

Only make bets that you can lose. Most of the things you try are not going to work, certainly not the first time. You need a plan that outlines how you will try to do this in a variety of ways. So I’m going to do a lot of small tests. I’m going to try a lot of small things. Don’t put all your chips on any one bet.

When things don’t work, when you’re surprised, don’t reject that and say, “That’s an outlier. I’m not going to worry about that. Find ways to take advantage of unexpected outcomes. Sometimes you can trade information with others: I came across this someone who can’t use what I’m working on, but it sounded like they might be a fit for what you are developing.” Figure out who else could help the person you were talking to, or how you could in some way leverage what you learned.

Many startup stories begin with an entrepreneur having a vision. “I had this idea and I worked hard and it worked out pretty much as I predicted.” The stories I hear at the Bootstrappers Breakfast tell of a much bumpier ride on winding roads with backtracking. For the most part, you are traveling through fog at night with fragmentary directions and no map. You have a flashlight that allows you to see a few steps ahead, but it’s hard to see too far. So I like Sarasvathy’s suggestion to focus on what you know and what’s under your control. If you want to be on time, leave early. Have a backup plan and maybe a Plan C if the backup doesn’t work.

Some of this echoes what Ash Maurya says in “Running Lean”, that it’s about iterating from Plan A to a plan that works. By definition, the plan that you make at the beginning of your startup is rarely the plan that you end up executing. But writing it down, doing a Lean Canvas or whatever you prefer, allows you to say, “Based on what’s happened, I’m going to make these changes and see what I learn next.”

Seth Godin: Don’t Run Out of Time or Money

“When we run out of time or money, we’re done. If we’re done before we’ve made an impact, the entire effort is wasted. Living in surplus creates long-term advantages. The process is simple but easy to forget: overwhelm the smallest viable audience with a solution that creates the conditions for them to take action. Repeat.”

Seth Godin “This is Strategy”

Seth Godin’s “This Is Strategy” is insightful but disorganized. It is essentially a collection of more than 300 of his blog posts, one to a chapter. But there are many valuable nuggets of insight, and I like this one in particular because it recaps several key points in common with the other books we are discussing.

You have to play a long game. You need to take small steps so you can move quickly and achieve results that you can build on. Start small, pick the smallest viable market to begin, get them on board, and then use it as a base camp.

Michael Gerber’s “The E-Myth Revisited”

- Business needs: Technologist, Manager, and Entrepreneur

- Technology not enough: Defined Process -> Franchise -> Scale

Drucker also emphasized that innovation was about more than technology. You need to understand the entire process that’s required to create a customer. How do you find or attract prospects, help them evaluate your offering, assist and encourage their first purchase, and then provide support in the context of an ongoing business relationship? A technician mindset is required to execute the core value stream, which needs to be managed, and the business also requires an entrepreneurial mindset to foster improvement and innovation.

If you want to grow, you have to be able to execute reliably, to bring in and train other people, to navigate the challenges of scale, and to continue to innovate. When he says franchise, he means a set of instructions or a documented approach that others can follow without needing your direct guidance at every step. The E-Myth Revisited is an old book that remains popular because it offers entrepreneurs key insights.

James Austin, MD: “Chase, Chance, and Creativity”

- Random chance affects everyone.

—-Other kinds of chance can be cultivated—– - Become more energetic, more active, organized and methodical to increase your luck surface area.

- Leverage your domain knowledge to see what others miss.

“Chance only favors the prepared mind.” Louis Pasteur - Leverage your hobbies and diverse interests (especially if they draw on sources distant from your target niche) for insights and innovations you can apply. Austin calls this altamirage.

Austin suggests three kinds of approach to cultivate luck above the level of random chance

- Kettering model: Being energetic, active, and methodical increases luck.

- Pasteur model: Domain expertise helps spot what others miss (“Chance favors the prepared mind”).

- Disraeli method: Unique passions or hobbies intersecting with primary focus create breakthroughs.

This is a very interesting book that recounts Austin’s efforts to uncover the causes of a number of rare developmental disorders. He shares his efforts to chase down mechanisms of action that would allow him to find cures. This book was his effort to make sense of why he was successful by drawing lessons from both his own medical research efforts and the work of other innovators.

One aspect of luck that he demonstrates in his narrative is that he cultivates a wide range of personal and professional relationships, and he is scrupulous about sharing credit and thanking everyone who assisted him with pieces to the various puzzles he was working on. He has written several books on Zen meditation that I also found very thought-provoking.

Seth Godin on Consistent Actions that Cultivate Success

- Think ahead and reason back: know where you want to end.

- The empathy of a mutual win: trade favors.

- Follow through on commitments and threats: be consistent.

- Use your unique knowledge, others may have unique knowledge.

- Encourage cooperation through repeated interactions and reciprocity.

- Build scaffolding: make it easy for others to come on board.

- Create simple and useful metrics for status and stick with them.

From “This is Strategy” by Seth Godin.

You have few resources compared to your competition, which means you have to establish clear goals. You can adjust as you go, but you are aiming for a sequence of small wins. Finding ways to help others and trade favors to create mutual wins extends your reach. In particular, you have to be looking for win-win deals with customers and partners so they are motivated to continue to collaborate. You don’t have to take a highly unfavorable deal, but you don’t start with a lot of leverage and need to aim for what is possible.

When you make a commitment, you have to follow through, and so you should be very careful in the commitments that you make. This care applies triple to threats. You have unique knowledge and insights that you can take advantage of, but you must remain mindful that others often have unique information and knowledge that you don’t have access to. You can’t always determine their view of the chessboard and the moves they can make that are not available to you.

The way to encourage cooperation is to aim for repeated interactions where you demonstrate your commitment to helpfulness. Always assume you will meet people again and they will know the truth of what happened the next time you interact. This is sometimes called a “give to get” mentality.

Make it easy for prospects to evaluate and deploy your product. Help them avoid problems. It’s often the case that your first few customers, the ones who are willing to take a chance on a startup, are more skilled at evaluating and adopting technology. If you remember the “Diffusion of innovations” or “Crossing the Chasm” terms, they are early adopters or visionaries. They buy your product because they “get it,” not because you sold them. They make it seem easy. Don’t be fooled; keep filing the rough edges off your product.

The best metrics for status based on the value the customer is paying for. When MCI went up against AT&T, every bill they sent showed the savings versus what they would be paying if they had stayed with AT&T. Customers are paying for your product to get results they care about. You should know what those results are before you take their money for the first sale.

I see some marketing and sales experts advocate for tracking feature usage or time spent using your product. They suggest you pester customers to use more features. These are often terrible ideas. Customers want results in as little time and effort as possible. A customer who uses six mouse clicks to get a result in three minutes is likely to be much more satisfied than one who spends an hour on the same task. Think about what the customer wants at the end of the journey.

It may help you to know which features they are not using, but you have to approach this lack of uptake from their perspective. Are they using other tools to solve some problems, and don’t plan to use your product? Involve them early in the design of new features and feature upgrades. “Running Lean” stresses the need to understand how the customer views the problem; that perspective should inform your product design.

22 Immutable Laws

People consume a description before they try to use the product

- Law of Sacrifice: Give things up to gain focus—narrow your product line, target market, or messaging to strengthen your position.

- Law of Attributes: For every attribute an incumbent has, there’s an opposite one you can claim (e.g., if “strong,” you can be “gentle”).

- Law of Candor: Admitting a negative can be turned into a positive if framed correctly (e.g., Listerine’s “taste you hate” campaign). Also make positive claims more believable.

Again, you’re up against guys with more money and with a better set of relationships with existing customers. You’re going to have to narrow your focus. You’re going to have to sacrifice so that the message you’re putting together, the demo, the brochure, is more likely to resonate. Don’t use the word “or” in the product description. Pick one approach. Don’t write in the future tense: don’t say “we will be able to do X.” Say “we do X today, would you like to see it in action?”

Pick one or two areas where you are going to differentiate from current alternatives. If those are not important to the prospects you are talking to, have conversations with at least 15 to 20 to make sure you need to abandon that approach and find a new one. Don’t try to match features with an incumbent, you don’t have the time or resources. It’s OK to say, “Sounds like you have made a good choice, we cannot support that today.”

Admit limitations to build credibility. When you are forthright about what you cannot do, they are more likely to believe the other claims you are making. Once you start to erect this little Potemkin village where you tell them something is ready or almost ready you trade a small disappointment immediately for a deal you invest effort in but are never able to close, or worse, a customer who pays but is not satisfied.

Unique Expertise & Relationships Drive Adoption

Three Kinds of Working Capital Needed

Three Kinds of Working Capital Needed

- Financial Capital

- Tools, equipment

- Intellectual Capital

- Skills, recipes, and know-how

- Trademarks, patents, copyright content

- Social Capital

- Relationships: customers, partners, suppliers, employees

I wrote this book because there was this huge emphasis on financial capital for getting a startup off the ground. Even when people talk about bootstrapping, they tend to focus on money, revenue, and how do you get there? As if all that’s needed for success is enough financial capital. That’s the working capital you need.

And the reality is skills, recipes and know-how are also essential for success for most startups. Figuring out how to cultivate those and how to improve your expertise is critical. Social capital, your ability to work with people, to develop a positive reputation, goes a very long way. You are starting over and you have to establish new relationships to prosper. You have to be helpful, you have to be you have to get out there and talk to strangers, which I can appreciate may be something you hoped to avoid by starting your own firm.

Closing Thoughts

Innovation is the first reduction to practice of an idea in a culture.”

James Brian Quinn

Culture matters. Stop working from idea to culture

- Start with culture (Niche)

- Analyze needs (Pain)

- Determine what constitutes proof

- Find an “In Culture” partner to help jointly reduce to practice

Questions From Audience

Q: First of all, I really enjoyed the talk, it was really interesting. I took away some things that I’m hoping to implement. Some of them were kind of obvious to me. Some of them not obvious at all. So I really appreciate you taking the time to walk us through this. I have one more question. I haven’t read any of these 12 books, is there a particular one that I would start with to help me prepare for starting a company?

I think the first edition of Saras Sarasvathy’s Effectual Entrepreneurship from 2011 is probably the best place to start. It’s about 200 pages but has many good diagrams. It’s a textbook, so buy it used for a few bucks. The later versions get much longer and are much drier. Here is a review I wrote on Amazon for Effectual Entrepreneurship.

Effectual Entrepreneurship offers a practical guide to how experienced entrepreneurs navigate the trade-offs and challenges in bringing a new product to market. It suggests a blend of planning with intelligent improvisation in the moment to new developments based on the means that you have already gathered. It stresses the importance of relationships: “Entrepreneurs create the future by working work together with a wide variety of people over a long period of time. […] Entrepreneurs create enduring human relationships that outlive failures and create successes over time.” Highly recommended for the principles and conceptual framework that allow you to react intelligently to events and create the future.

My second choice would be Running Lean by Ash Maurya, which also offers a holistic perspective on the challenges of getting to product-market fit. His books get better as he revises them, so I would pick up the third edition from 2022, but all three are good.

Third would be “The Mom Test” by Rob Fitzpatrick. It’s a quick read and has a nice conversational style. Fitzpatrick is candid about a number of mistakes that he made. Actually, most of the books on this list are confessionals; the authors share the mistakes they have made and explain how they hope you can avoid them. I find that style much more useful than the startup books where the author says, in effect, “Here’s how I made a million dollars. You can too if you do exactly as I say.”

So my top three for someone starting out would be

- Effectual Entrepreneurship (2011 edition, used) by Saras Sarasvathy

- Running Lean (any edition, but 2022 is quite good) by Ash Maurya

- Mom Test by Rob Fitzpatrick

Q: The most surprising thing for me was that I had only heard about half of these books. The Effectual Entrepreneurship book doesn’t seem like it’s been read by many people even though it’s been around for a while. I was disappointed there is no audio book version. I was really interested in reading “This is Strategy” by Seth Godin, but there a lot of negative reviews. reviews about that one, so I’m probably gonna skip that one, even though it seems like there’s some nuggets in there.

Candidly, the Godin book is a mess. I did a review for our book club at “Seth Godin: This is Strategy, Make Better Plans” that’s 2,000 words and pulls out what I thought were many of the better insights for entrepreneurs.

Related Blog Posts

- Chalk Talk: S-Curve for Technology Investment

- Chalk Talk: Sarasvathy’s Effectuation Model for Startups

- Saras Sarasvathy’s Effectual Reasoning Model for Expert Entrepreneurs

- Seth Godin: This is Strategy, Make Better Plans

- Be Wary of Attacking a Walled City

- Articles, Ideas, and Books That Made Me a Better Entrepreneur

- Chalk Talk 1-2-4-1 Model

- Jerry Weinberg interview

- 12 Books For the Busy CEO Tonight (Mon Dec-11-2006) @ SDForum

- 12 Books For the Busy CEO – Feedback

I used the Josh Billings quote in “Entrepreneur as Detective.”

This was republished on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/12-books-busy-founder-sean-murphy-5ksrc/