This is a practical overview of social capital, an essential concept for entrepreneurs despite being hard to measure. I offer suggestions for growing your business network, and enhancing your reputation, explaining why increasing social capital creates value for your startup.

A Practical Introduction to Social Capital for Entrepreneurs

Businesses require financial capital to get started, in addition to domain knowledge and an ability to execute. But entrepreneurs rely on both existing trusted business relationships and their ability to cultivate new ones, even as they continue to refine and extend their domain knowledge.

Businesses require financial capital to get started, in addition to domain knowledge and an ability to execute. But entrepreneurs rely on both existing trusted business relationships and their ability to cultivate new ones, even as they continue to refine and extend their domain knowledge.

What is Social Capital?

“Social capital is the set of business relationships that have been established with customers, partners, suppliers, and prospects. These business relationships enable access to domain experts, introductions to potential cofounders and early employees, and conversations with prospects who may become early customers.” – Sean Murphy in Working Capital Vol 1: It Takes More Than Money

It’s as much about who you know and as it is how you know them. These contacts could come from:

- Family, friends, and acquaintances

- The firms current suppliers, partners, customers, and advisors

- Co-workers, customers, and suppliers from prior employment

- Alumni: classmates and teachers from high school, college, and university

- Industry, professional, or association memberships

- Permission to contact lists (e.g., mailing lists)

Knowing how to leverage that social capital is key for finding prospects or other experts or partners. So maintaining your good standing in various communities and business networks makes a difference.

Trust

Trust is an essential element to establishing and maintaining a business relationship, either at a personal or organization level. It’s at the core of developing good social capital. Trust is built slowly over repeated interactions where entrepreneurs deliver time and again, the results that they promised. And many entrepreneurs get a jolt in their new venture when they discover that their credibility with strangers, which was once freely granted by virtue of their employee, must now be earned one painstaking step at a time.

Good standing in the professional world is less about personality and likability, and more about authenticity and predictability. You are trustworthy to the extent that your actions are predictable and your words align with your actions. This means that you follow through on your commitments. In most situations, the product’s performance or service results will always make a bigger impact than individual personality.

Another aspect of trustworthiness is being committed to creating value for the customer. You have to be committed to win-win solutions. Making money at the expense of your customers’ happiness is not good business. It’s not a win-win. And it’s not something that’s going to build trust and lasting business relationships you can rely on. Our advice: ask customers for feedback and focus more on constructive criticism than praise or general complaints.

Social Capital Helps You Find Prospects

Entrepreneurs need trusted feedback to evaluate your business concept, product ideas, or early product iterations. These business relationships enable access to domain experts, introductions to potential cofounders and early employees, and conversation with prospects who may become your early customers.

Even if your connections are outside your target industry or market, I guarantee their social spheres will include at least someone relevant to your business. Everyone knows many people: your challenge is to help them identify potential prospects. You do this by talking about your experiences with this problem and describing the problem so that they can consider who else they know who may have this problem or need. The more specific the description, the more likely you are to receive suggestions, recommendations, insights, and referrals in return.

The temptation is to describe things in a very general way or to talk about the capabilities that you offer. This acts as an IQ test: can you help me figure who can use this? It is better to be very specific about the customer you want to serve and the problem or need you address.

Startup entrepreneurs typically face one of two challenges. Either you’re developing something novel, trying to fulfill an existing need in a new way. Or you’re trying to fulfill an existing need through an established way but perhaps with some differentiation. If you’re developing a new solution, then you want to focus on who’s in pain or who has experienced the problem that you address. People tend to prioritize finding a big market or large audience. While that may be important in the long run, in the beginning, it’s far more beneficial to identify a clear niche that is in a lot of pain and is willing to pay to have their problem solved. If you’re working on improving an existing solution, then the question is not, “is there a need?” but, “how am I different?” In which case, you want to talk to people that have paid for a similar service or product and interview them.

Otherwise, entrepreneurs fall into a trap where they describe their product or service by saying, “anybody could benefit from this.” Or they target generic categories saying, “small and medium firms would benefit from this.” No one ever defines themselves as a small/medium business person. Instead, they say that they run a shoe store or own a restaurant. The goal is to be as specific as possible by describing your business as a solution to a particular problem, not as a list of features. “Contact CRM,” “mobile responsive pages,” and “SEO optimization” are not as appealing as “easily build and market your own website, no software experience necessary.”

Another activity I recommend is to write an “origin story” for your business. Make a write-up of your direct experiences with the problem and be very clear about why you think there’s an opportunity, how your services differ, and who exactly you want to serve in the future.

Talking to Prospects

There are two postures for approaching prospects. First, there’s the problem-focused conversation, where you want to outline the parameters of a good or bad offering. You’re talking to people familiar with the problem and have used similar services products in the past. And usually, the easiest way to approach someone for that conversation is to be candid and say, “Look, I’m thinking about starting a business in X. I wonder if I could get five or ten minutes of your time to talk about your experience with X.”

Assume that the majority of people you talk to are introverted. Before a face-to-face meeting (or Zoom call), send an email outlining 3-6 questions. And be prepared for the conversation to end in five or ten minutes. If they don’t want to talk very much, learn what you can and end the interview. If they’re energized and passionate about the topic, still end the conversation after ten minutes, but then follow up with another request to meet. It’s much easier to have that quick conversation and then say “I need another 10-15 minutes of your time,” than to draw out your initial interaction and completely exhaust their patience.

The second posture is value-focused. And the only way to delve into pricing and value questions is to make real offers. You gain much more insight when you ask,“would you pay x for this?” instead of “how much would you pay for this?” Again, just like identifying your target customer, you want to be as specific as possible–talking in the abstract just doesn’t work. Your offer needs a deliverable, turnaround time, and price. You want your price to be high enough to be credible, but low enough to be a variable. You can always raise your price later depending on feedback, but be warned: it is very difficult to raise your price with the same individual.

When we talk about approaching prospects, it connotes individuals. But don’t underestimate the marketing potential of an established firm. An entrepreneur who has attended several of our Bootstrapper Breakfasts® has started a business that melds VR with furniture shopping. His customers can visualize how different desks and tables fit in their house. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, offices were shut down, and some employees were left without an office space or desk. Google was one of multiple companies to offer a desk renting service to its employees. He capitalized on that, approached Google at a department level, got a foot in the door, and is now benefiting from the company’s container of employees and established reputation.

This is often called a “land and expand” strategy, where entrepreneurs deliver value for a group and move sideways within the firm. You still need to identify your prospect clearly and deliver a concise offer. But now it’s easier because the customer and prospect work at the same firm.

Finding Cofounders

The cofounder rule of thumb is “shared values, complementary strengths.” Many of the serious arguments between cofounders stem from overlapping strengths. Two people are both really strong in one area, and weak in another. And so there’s conflict over the overlapping strengths, their common weakness is completely overlooked, and now everyone’s disappointed. The easiest solution is to bring a third person onboard who can compliment your skills and expertise. If you’re more of a business person, then you probably have to find a technical person. If you’re more of a technical person, you’re going to have to find somebody willing to talk about the business and do some sales and marketing. If you find yourself leaning towards ADHD, you may need a partner who is more focused.

But these complementary strengths need to exist within shared values.

Determining whether you can share a race car (or perhaps a mini-sub is a better metaphor) with someone is complicated takes time. I recommend talking to several people in parallel, and collaborating on small projects. These projects should act as pressure tests, to see how people react to deadlines and stressful situations. If you haven’t already, divide expenses and client payment before agreeing to become a cofounder. You don’t marry someone after the first coffee date, right? Go on a real date, then deepen the relationship as events warrant.

Entrepreneurship is a very popular topic. Most of Silicon Valley want to be identified as entrepreneurs, but very few of them are actually willing to leave their jobs and take that risk. So you want to make sure your cofounder is someone who will get in the race car with you, run the course, and accept the possibility of a crash.

Similarly, you have to make progress on your startup alone. Relying on a cofounder to kick-start your business is not an attractive model. Do something–build an Excel model, a WordPress site, attend a Bootstrappers Breakfast and start narrowing down your customer base. Cobble together something that you can show to attract prospects and potential cofounders.

Tips for Social Capital Building Conversations

Calling in favors in the business world is a complex undertaking. These interactions can alter depending on both cultural norms and how well you know each other. Engineers, for example, would look at things differently than sales reps. To avoid any messy confrontations, here are my general rules for “spending” social capital.

- Maintain your network: do favors when asked, if you can, or say no promptly. The fact that you were helpful will become known not just to the person you did the favor for but others in the same branch of your network. Keep people up to date on an annual basis about what you are up to and share relevant information about others they may be interested in every 6-12 months just to stay in touch. In the long run if all you do is ask for favors you will burn friends and associates out.

- Be as specific as possible in your request: for example, “I am working on a team that has recently developed an application that can be used by church choir directors who need to search for music by different criteria–for example by the number of different singing roles. If you know someone who is responsible for managing a choir I would appreciate an introduction.” Some phrases that people use that are not helpful in narrowing the search to reply to your request:

- “Small business” Better would be a company doing between 2 and 5 million dollars a year in revenue, or a company with between 10 and 50 employees, or two or three specific criteria that indicate exactly what you are trying to reach.

- “Need our product” => “has this problem” phrase the request in terms of needs or problems that a target prospect would know that they have.

- “Need a technical person” Better is to list a specific set of skills or accomplishments: for example, know Python, has built websites in WordPress, is an attorney who has supported other software startups…

- Contact a few people at a time: a mass mailing seems like it is much more time efficient than contacting people individually by phone or e-mail but personal request is far more energizing and likely to earn a response. There is another failure mode that an occur when you blast your 400 LinkedIn connections with a request: you can so many responses you do not reply in a timely fashion and you actually damage the relationship because it appears that you are ignoring them.

- Don’t try to run two or more searches at once: pick the most important conversation you are trying to have next and focus on that. A request that says I am looking for a cofounder like X and an early adopter customer like Y and an investor is unlikely to generate any action.

- Close the loop: always let people who make a suggestion or an introduction know the outcome. Say thanks

- Avoid a guilt trip. Don’t start the conversation with “Since I helped you in the past with X, could you help me with Y?” Whether or not you helped someone in the past, assume they don’t owe you anything. Instead, say, “Hey, I could really use a favor. Here is specifically what I would like.

- Understand the opportunity cost to them. For example, if they own a piece of equipment that is earning them $10,000 a week, asking to borrow it is going to be a huge inconvenience on their part. On the other hand, if you notice that the machine has been largely unused (for example, it’s been under a tarp for the past 2 months) then loaning it to you for a couple weeks will be much less costly for them.

- Take no as an answer. This is obvious to most, but in case it isn’t: know that you need to accept a “no” without getting frustrated. If you ask someone for an introduction and they refuse, you need to accept their answer graciously. If you end the conversation on a positive note, you can come back in a few months and say, “I’ve made a lot of progress. Can I give you an update on where we are?”

- When you return a favor, make the benefit match the earlier cost. Leveraging social capital requires you to understand the cost you have imposed when someone does you a favor, and the value of what they have done for you. How much would it have cost in time and effort if you had not been able to call in a favor. You don’t have to return a favor immediately and you don’t have to ask for one in return soon after someone helps you. But you need to calibrate the cost (to them) and value (compared to your next best option) and make sure things balance out over time.

- You don’t have to wait for them to ask for a favor. Some people are shy about asking for a favor. If someone did you a solid favor, keep current on their needs and situation and actively offer to assist them in ways that will help move their business forward. Note: giving someone free advice is not returning a favor.

- Be mindful that you are borrowing credibility when someone makes an introduction. When you ask a friend for an introduction, it’s like borrowing a guest pass. If you behave poorly the third party will not only hold it against you but against the person who made the introduction. If things go wrong during your meeting or phone call, and you’re rude or impolite, that negatively affects their attitude towards your friend as well. By the same token, this allows you to ask the person who introduced you to check in for unbiased feedback (because their credibility is on the line).

- Join a community of entrepreneurs. In general, you’re not going to be directly competitive with most members, and you will see many opportunities to collaborate.

Most people are looking for help on business critical issues that are important to their company. But recognize that if you’re working on something which is not a critical issue, it might be better to end the conversation. People are very interested in what you have to say if they know–and trust–you can match the value of their help.

Reputation is Measured in the Context of a Group

It’s a mistake to assume that 500 or 1,000 or 4,000 LinkedIn connections automatically equate to a tremendous amount of social capital. It’s indeed extremely helpful to have many contacts and business relationships. But what transforms these relationships into capital is your understanding of how each person relates to different groups and how they interact (or don’t) with each other.

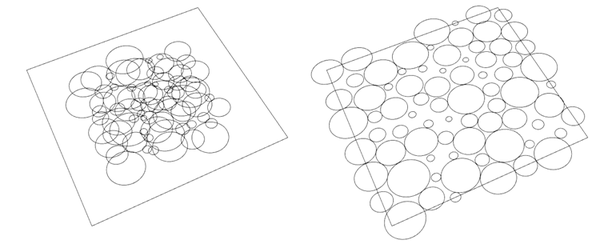

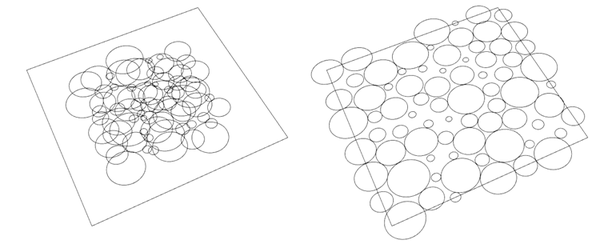

This diagram by Valdis Krebs explains the messy reality of group membership and relationships in a thriving society. The diagram on the left shows that people are members of multiple overlapping intermingled groups, with subgroups and niche communities nestled inside of larger groups and communities. The initial conception, shown on the right, is of clean membership in groups that don’t overlap. This can occur if you look for “mutually exclusive collectively exhaustive” discriminants to separate people into categories but does not represent how people who come to know each other choose to associate. Christopher Alexander has explored this complex interaction between people and their membership in groups–referring to the arrangement on the left as a semi-lattice–applying it to city design in his essay “A City is Not a Tree.”

After your family and a small group of close friends, the smallest group that you are a member of is your workgroup or tribe–the small team of individuals you work with daily. That team operates within a company, a self-contained economic unit that provides you with income. If all your meaningful business connections are within that one container, it will be very difficult to leave the company. And if you part on less than friendly terms, you might lose access to most or all the people in that container. Then there is the industry container, where multiple companies compete around the organizations of customers and suppliers.

In addition to your company, other large groups you are normally a member are

- an industry: a collection of companies who share common business activities and sources of revenue.

- a community of practice: people engaged in shared learning on a topic where you enhance domain expertise by interacting and collaborating with other experts in the same field.

- a geographic community: the people you typical encounter due to shared physical proximity.

- an affiliation network: voluntary association with others who have shared values, interests, or goals; for example, an alumni group, a church, a hobby group, or a charity.

Those 4,000 LinkedIn connections are incredibly valuable, but each one represents a different relationship with its own context. (Some of your connections might even be competitors.) Don’t assume that every relationship can be leveraged equally. And realize that early success in one container won’t necessarily scale once you leave. Be curious–work to understand where other people’s needs and objectives overlap, merge, or operate in tandem with yours.

Beware of Overlap Between Current or Former Employers and Your Startup

Under California law, what individuals do on their own time, with their own materials or resources, is their property. Other states have different laws, so the first step entrepreneurs should take is to familiarize themselves with those legal constraints and maintain a clear separation between company property and what you use for a new venture. My rule of thumb: only take what’s in your head.

Avoid competing with your company if possible. Start something that is complementary to your company, or that only competes with a small aspect of the company’s products or services. Consider targeting your old firm’s setup requirements–what they need to get started–or focus on opportunities they have enabled after they have sold their product or delivered their service. It’s usually safer to strike out in a new direction and avoid the mess of ethical and potential legal problems altogether.

Your regular work hours need to be reserved for company-related work. Before work, lunchtime, after work, nights, and weekends are all available depending on how your regular work hours are defined.

If you are unemployed, then you can talk to people anytime. Though, it’s still probably not a good idea to compete directly with your former employer, especially if you’ve parted on not-so-friendly terms. Previous contacts from that former employer will be more likely to help if your venture is not in direct competition with their work.

Your first conversations should provide insight into whom your service or product is going to serve. You want to reach out to people that either look like a potential customer, are that potential customer, or who have previously worked with that potential customer. Essentially, look for either real prospects or people that have direct knowledge of those prospects.

Summary

- You have to network. For a venture to succeed, you have to go out and ask questions. Talk to people who are either proxies for your customer or real prospects. And remember that every fruitful professional relationship has elements of shared success, reciprocity, and predictability.

- Be specific when talking to people, whether you’re looking for prospects or giving an offer. That ensures you receive specific feedback and critique in return.

- Focus on proving your idea provides value first, then start recruiting cofounders and partners. Be certain you’ve identified a real opportunity before trying to enlist others. Gather evidence that people will pay for your service or product. Now you can offer it to others as proof that you can make progress on your own and that they should join you.

- Make offers early. Once you think you’ve got a handle on the problem, start to make offers. While those offers may or may not be accepted–all too frequently they are not–they help you iterate faster and narrow your business focus to hone in on a particular niche. It’s easy to speculate and theorize. Do the hard work of talking to prospects and making offers; these are the only way to gain answers and insights.

- Individual personality plays a small role. Likeability is a factor, but the real need is to make commitments carefully and then follow-through and deliver.

We Can Help

Related Blog Posts

- Treat Social Capital With the Same Care as Cash

- Five Tips For Activating Your Network of Relationships

- P. T. Barnum’s Golden Rules For Making Money

- Ford Harding on Rules of Thumb for Networking

- Early Sales Efforts Foster Value Co-Creation

- Building a Business Requires Building Trust

- Honesty in Negotiations

- Preserving Trust And Demonstrating Expertise Unlocks Demanding Niche Markets

- Selling to a Business Requires Conversations that Build Trust

- Successful Bootstrappers Are Trustworthy Salespeople Committed to Customer Satisfaction

- Keeping Your Customers’ Trust

Working Capital™ Series

- A Primer on Business Assets for High Technology Startups

- A Practical Introduction to Financial Capital for Bootstrappers

- Basics of Intellectual Property for Bootstrappers

- A Practical Introduction to Intellectual Capital For Bootstrappers

- A Practical Introduction to Social Capital for Bootstrappers

- Building, Borrowing, and Keeping Trust

- Taking Stock of Your Business Assets

- How to Leverage Current Business Assets For Growth

- A Holistic Approach to Launching a Bootstrapped Startup

Image Credit: Network Globe by Jozsef Bagota; licensed from 123RF.

Pingback: Bob Biglin’s Review of Working Capital: It Takes More Than Money -